Custis Garden Archaeological Report, Block 4Originally entitled: "A Garden Inferior to Few: A Proposal for Archaeological Investigation of the Custis Garden"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1071

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

"A GARDEN INFERIOR TO FEW"

A Proposal for Archaeological Investigation of the Custis Garden

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author of this report would like to thank the following persons for their contribution to the preparation of this report: Blanton McLaine, Librarian at Eastern State Hospital for use of the Hospital's Galt papers, Mrs. Audrey Noël Hume for providing maps and answering questions about the 1960s archaeology, to Hannah McKee for creating the maps & production details, and to Tamera Mams for some of the photographic work.

| Introduction | 1 |

| Property History | 3 |

| John Custis and his Garden | 3 |

| The Second Half of the 18th Century | 4 |

| Custis Square During the 19th Century | 6 |

| The 20th Century | 10 |

| Previous Archaeological Investigations | 16 |

| 1964 Excavation | 16 |

| 1968 Excavation | 19 |

| Rescue Archaeology | 19 |

| Special Testing | 20 |

| Archaeological Potential | 22 |

| Conclusion | 25 |

| Endnotes | 26 |

| Bibliography | 27 |

| Appendix A - Proposal for Archaeological Research and Budget | 33 |

| Figure 1.The Frenchman's Map | 3 |

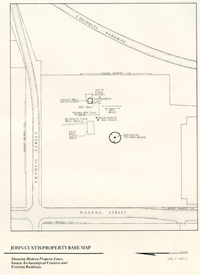

| Figure 2.John Custis Property Base Map with Frenchman's Map Overlay | 7 |

| Figure 3.The Desandrouins Map | 8 |

| Figure 4.The St. Simons Map | 9 |

| Figure 5.The Custis Property, Showing its Use as a Park | 10 |

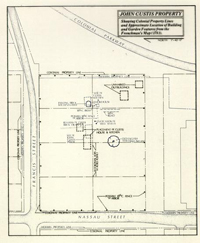

| Figure 6.John Custis Property Base Map with Hospital Buildings Overlay. | 11 |

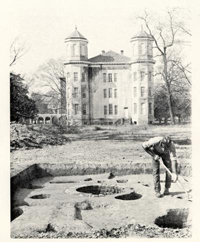

| Figure 7.The Thompson Building | 12 |

| Figure 8.Building 22 | 13 |

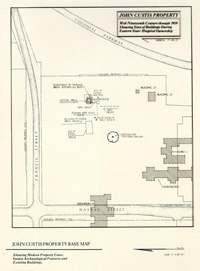

| Figure 9. John Custis Property Base Map | 15 |

| Figure 10. Cross-section of Rubble Fill through the Custis Cellar | 16 |

| Figure 11. Excavation around the 19th-Century Custis Kitchen | 17 |

| Figure 12. Overall View of 1964 Custis Excavation, Showing Two Wells | 18 |

| Figure 13. Series of Postholes Forming a Possible Garden Arbor | 23 |

INTRODUCTION

In the future, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation may undertake reconstruction of the John Custis property (Block 4, Colonial Lots 1-8). For this reason, background research on the potential for archaeological remains relating to the 18th-century house and gardens on the property was conducted by the Department of Archaeological Research. In his upcoming book on Virginia gardening, Peter Martin has described John Custis, the creator of these gardens, as "among the boldest and scientifically most curious promoters of Virginia gardening and horticulture" in the first half of the 18th century (Martin, in press:73). Although this report will focus largely on the remains of Custis's house and gardens, other aspects of the property's history will be considered, particularly as to how they relate to the archaeological integrity of the site.

John Custis IV, owner of the property from circa 1714 to 1749, built his brick house on a high ridge along the perimeter of Williamsburg sometime prior to 1717. Although apparently constructed in a Jacobean style not commonly seen in Virginia colonial buildings (A. Noël Hume 1984), it is not Custis's house which formed the most important aspect of his property. Custis was quite an avid gardener, and the garden he created at his house was apparently rivaled in Williamsburg only by that of the Governor's Palace.

Through documentary research, this briefing will try to determine the potential for significant archaeological research on Colonial Lots 1-8. Deeds, inventories, personal correspondence, and contemporary maps of Williamsburg were used to compile a picture of what the Custis Square looked like during the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. Later disturbances which may have impacted upon or destroyed the 18th-century archaeological record were also taken into account to formulate an assessment of the archaeological potential of the property. Areas where chances are good for intact archaeological remains, particularly those associated with the Custis garden, are defined.

Within the past decade, advances in archaeological research and methods have made great strides in the delineation of colonial garden plans and plant material. Recent work by the Colonial Williamsburg Department of Archaeological Research on the Peyton Randolph, Tazewell Hall, and Shields Tavern properties have revealed evidences of garden beds, most likely used for growing vegetables (Edwards et al.1988; Samford et al. 1986; Higgins et al. 1987; Brown and Samford n.d.). Evidence of garden layout and design have also been recently seen in excavations at Carter's Grove (Kelso 1972), Bacon's Castle (Luccketti 1987), Monticello (Kelso 1984) and in Annapolis, Maryland at the William Paca House (Leone 1986) and the Calvert House (Yentsch 1984).

Advances have been made, not only in the greater awareness of the landscape and use of space, but also in the development of archaeological and paleobotanical 2 techniques, such as phytolith and pollen analysis, which furnish valuable information on plant remains. This report will also briefly examine these advances and how they may be applied to garden research at the Custis Site.

At the present, there is some confusion concerning the 18th-century appearance of the Custis House. The cellar and some of the area around the house underwent archaeological investigation in 1964. Additional excavation around the house may define the orientation of the house and particular architectural details.

Included with this report is a preliminary proposal and budget for archaeological excavation on the Custis property (Appendix A).

PROPERTY HISTORY

Since a complete history of the Custis Square has been prepared by Mary Stephenson (1959), only details which have relevance to potential archaeological remains on the property will be discussed here.

Figure 1. The Frenchman's Map. Arrow at lower left points to the Custis Property

Figure 1. The Frenchman's Map. Arrow at lower left points to the Custis Property

John Custis and His Garden

The Custis property, consisting of eight one-half acre lots, is located south of Francis Street and east of Nassau Street (Figure 1). This property, located on a ridge between two ravines, was home during the first half of the l8th century to John Custis IV (1678-1749). Custis purchased the lots around 1714, moving into the town of Williamsburg from his plantation on nearby Queen's Creek. Within three years he had constructed a brick dwelling, known later as the "Old Six-Chimney House" (Cocke 1844) and had begun to create a garden on the property which Custis described in 1734 as "inferior to few if any in Virg[ini]a" (Custis Letter Book). Although the layout of this 4 garden is not documented, Custis's correspondence with Peter Collinson, English botanist, between 1734 and 1746 furnishes some clues about the nature of the garden (Swem 1957). Their letters reveal that Custis was growing fruit and nut trees, such as peaches and almonds, from seeds and sets sent from England by Collinson. Custis also wrote to merchants in England requesting shrubs, such as holly and yew1, as well as flowers, bulbs, and roots2. There was certainly a formal aspect to some of Custis's garden, since a letter to Collinson mentioned shaped topiary and archaeological excavations revealed a number of large, elaborately decorated clay pots (A. Noël Hume 1974). Custis's correspondence suggests that the garden may have consisted of several components, including a formal garden typical of a man of his wealth and station, as well as an orchard for growing fruit and nut trees. References to flowers, as well as to a kitchen garden (Swem 1957:87), indicate that Custis apparently had sections in his garden devoted to these as well.

Further evidence of Custis's garden is recorded in William Byrd's diary which frequently mentions walking in Custis's garden during 1720 and 1721 (Wright & Tinling 1958), although it provides little actual detail about the gardens. Naturalists such as John Bartram also visited Custis's garden with favorable reactions (Martin, in press:78)

The Second Half of the 18th Century

After a lingering bout with ill health, Custis died in 1749 (Swem 1957:15). The property then passed to his son, Daniel Parke Custis, who probably visited but apparently never lived in Williamsburg. An overseer took care of the Custis Square lots and also the plantation on Queen's Creek while Daniel Custis was in possession of the property (Stephenson 1959:20). Although the overseer lived on the Queen's Creek plantation, there seems to be an indication that Custis's slaves were still occupying Colonial Lots 1-8 (Stephenson 1959:21). After Daniel Custis's death in 1757, his widow Martha married George Washington, who managed the property until Daniel and Martha's son came of age in 1776. Meanwhile, the lots were rented out to several different tenants, among whom was William Byrd III. Table I lists the owners and occupants of Colonial Lots 1-8 since the beginning of the 18th century.

Documentation about some of these tenants holds clues about potential archaeological remains on the property. For example, Peter Hardy ran a coachmaking operation and brass foundry on the former Custis property for a short time (1772-1774). Evidence of this short industrial phase should be apparent somewhere on these lots, in scatters of brass debris and other industrial waste. Another tenant, Joseph Kidd, who ran a lodgings at the Custis House in the early 1770s, placed an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette (June 20, 1771) which stated

… Gentlemen may be accommodated with good LODGINGS, exactly suitable to those who make Choice of Retirement after the Fatigues of Business. I have an excellent CLOVER PASTURE adjoining my House, well secured. Gentlemen may depend on being charged at the most reasonable Rates.5

| Date | Owner | Occupant |

|---|---|---|

| pre 1714 | unknown | |

| c. 1714-1749 | John Custis IV | John Custis IV |

| 1749-1757 | Daniel P. Custis | Daniel Custis (at times) |

| 1757-1778 | Daniel P. Custis est. | Mrs. Daniel Custis 1757-1759 |

| Bartholomew Dandridge 1760 | ||

| William Byrd 111 1762-1769(?) | ||

| Michael Smith 1770 | ||

| Joseph Kidd 1770-1772 | ||

| Peter Hardy 1773-1774 | ||

| James McClurg ? 1775 | ||

| 1778- | John Parke Custis | James McClurg 1778-1779 |

| 1779-1811 | James McClurg | James McClurg 1779-1783 |

| unknown 1783-1811 | ||

| 1811-1812 | Samuel Tyler | unknown |

| 1812-1818? | Samuel Tyler est. | by 1815 house inhabitable |

| 1823 | Jesse Cole | |

| 1824 | William T. Galt | William T. Galt 1824-1830 |

| 1843-1959 | Eastern State Hospital | |

In a letter dated May 11, 1778, John Parke Custis wrote to his stepfather George Washington that

…"as Williamsburg is declining fast, and the Houses on My Lots are in a wretched Situation; and are not fit to live in, and it will never be worth my while either to build or repair." (Lee)

He discussed selling the lots with Washington, and on November 27, 1778, the property was advertised for sale in the Virginia Gazette:

To be SOLD for ready money, by public auction. on the premises, on Monday the 14th of December, MY HOUSE and LOTS situated on the back street, and one of the most retired and agreeable situations in Williamsburg . The house is in tolerable good repair, having two good rooms and a passage on the lower floor. The offices are a kitchen and a large stable, with a meathouse, &c. There are about four acres enclosed in one lot, and will be sold with the house.6

JOHN PARKE CUSTIS.

Dr. James McClurg, who owned the Custis lots during the late 18th century, is believed to have purchased the property sometime around 1779 (Stephenson 1959:32). Land tax records indicate that McClurg owned the eight lots on Block 4 from 1782 to 1811. McClurg, however, is charged with a number of repairs to his Williamsburg property by carpenter Humphrey Harwood throughout that year. Since McClurg's repairs begin approximately one month after the announced sale of John Parke Custis's property, it is likely that McClurg purchased Lots 1-8 at this time. Another compelling argument for these repairs being to the former Custis property is Custis's letter to George Washington discussing the property's state of disrepair. McClurg only lived on his Williamsburg property for a few years, apparently renting out the house after his 1784 move to Richmond (Stephenson 1959:36).

Maps made during the Revolutionary War show the Custis property in varying amounts of detail. The Frenchman's Map of 1781 (Figure 1) shows four structures on the eight colonial lots. Figure 2 shows these buildings overlain on a base map showing the property as it is today, and its known archaeological remains. The central portion of the Custis Square was occupied by a large structure and a smaller outbuilding, which the 1964 archaeological excavations have shown to be the house and a kitchen. Two additional buildings are depicted in the southeast corner of the property; one of these may have been the stable mentioned in the 1778 Virginia Gazette advertisement. The entire Custis Square is enclosed with a series of dots, thought to represent trees. It is interesting to note that in a 1734 letter to Custis, Peter Collinson suggested that Custis plant rows of horse chestnuts "before your Houses next the street att Williamsburgh" (Custis Letter Book).

Another map prepared around the same time period, the Desandrouins Map (Figure 3), shows the same configuration for the house and kitchen, but with three outbuildings in the southeast corner of the property.

The only map which may indicate evidence of a garden on the Custis property is the St. Simon's Map (Figure 4). Prepared during the Revolutionary War, it shows three, or possibly four, buildings. Depicted to the west of the house is a fenced rectangle whose markings seem to suggest a field or plowed area. It is possible that this indicates the grazing pasture noted in Joseph Kidd's 1771 advertisement, or could represent the location of Custis's garden.

Custis Square During, the 19th Century

McClurg owned the property until 1811, when it passed into the hands of Samuel Tyler. The brick kitchen, the only structure surviving on the lots, was probably built around this time. After -his death, the property was described in 1815 thusly: "…the houses and lots in the City of Wmsburg called the 6 chimnies is in a ruinous and decaying state, the house not being habitable and can not be rented for anything" (Tyler, as quoted in Stephenson 1959:37). The house on the Custis Square reputedly burned during the early 19th century, although no documentary evidence has been located to confirm this. Archaeological excavations done around the ? and within the cellar of the house in 1964 suggest that this fire occurred around 1820 (CWF 1964).

The Lunatic Asylum, whose main building was located to the west, across Nassau Street, agreed in December of 1851 to purchase the Custis property, described as the six Chimney lot, for a sum of $661.00 (Gibbs and Rowe 1974:243). In January of 1853,

Figure 2 - John Custis Property Base Map

8

Figure 2 - John Custis Property Base Map

8

Figure 3 - The Desandrouins Map. Arrow at lower right points to the Custis property.

9

Figure 3 - The Desandrouins Map. Arrow at lower right points to the Custis property.

9

Figure 4. St. Simons Map. Arrow at lower left points to the Custis property.

the General Assembly appropriated the money which allowed, among other things, these lots to be purchased. A report prepared by Dr. John Galt in February of 1853 listing improvements to be made under the General Assembly appropriation mentions the former Custis property:

Figure 4. St. Simons Map. Arrow at lower left points to the Custis property.

the General Assembly appropriated the money which allowed, among other things, these lots to be purchased. A report prepared by Dr. John Galt in February of 1853 listing improvements to be made under the General Assembly appropriation mentions the former Custis property:

Improvements on the six-chimney lot. To enclose this with the simplest form of iron railing, will cost twenty five hundred dollars. I Would further propose the temporary employment of a skilful gardener, in the first instance, to lay out the grounds ornamentally, and secondly, the fitting up of the house now on the lot, for the future residence of a permanent white gardener; as both these measures would be required in carrying out a suitable system of improvement. The outlay for this purpose, would amount to about a thousand dollars. I think it doubtful whether anything could be advantageously entered upon at present in this direction, but would certainly recommend ultimate action of such character (Galt Papers).

That at least some of these plans were carried out is described in a document from the Galt collection, dated to the mid-19th century: "..the six chimney Lot..having..2 yew trees said to be there in General Washington's time are still adorning the Asylum garden into which this lot so rich in association has been converted" (Galt Family 10 Papers). The house that was mentioned on the lot in Galt's 1853 report may be the Custis Kitchen, although this would seem to be too small for use as a house. There has been no map or other document located at present which suggests another standing structure on the lot at this time. Mrs. Victoria King Lee, recalling pre-Civil War Williamsburg, indicates that the kitchen was used as a tool storage shed by Eastern State Hospital (Anonymous 1933).

20th Century

Figure 5. The Custis property, showing its use as a park.

Figure 5. The Custis property, showing its use as a park.

Aerial photographs taken in the mid-1930s (#76-1393) show the use of the property as a garden or park area (Figure 5). The 19th-century brick kitchen is seen standing along the eastern perimeter of the property and a large circular dirt path encompasses the lot, leading from the Thompson Building. The Thompson Building, a dorm facility, as well as several other smaller buildings, were constructed around the fringes of the Custis Square property during the latter half of the 19th century (Anonymous 1966), but do not seem to have had much impact on the main portions of the lot, where structures and the Custis Garden would be expected. Figure 6 shows the location of each of these buildings with respect to the 18th-century house and kitchen. Each will be discussed here in terms of the expected amount of damage to archaeological resources on the property.

Figure 6 - John Custis Property Base Map

Figure 6 - John Custis Property Base Map

Figure 7. The Thompson Building is seen to the west in this photograph of the 1964 archaeological investigation of the Custis property.

Figure 7. The Thompson Building is seen to the west in this photograph of the 1964 archaeological investigation of the Custis property.

Thompson Building - This large brick and stone structure was constructed in the latter portion of the 19th century and spanned what is now Nassau Street. It served as a dormitory and photographs show it as containing an English basement (Figure 7). The eastern end of this building extended into Colonial Lot I of the original Custis property, and chances for any remaining intact archaeological features and strata in this direct area are slim. The Thompson Building was destroyed in late 1967, after Eastern State Hospital had moved to its present home on the western outskirts of town(White 1967). Specifications for the destruction of the Eastern State buildings taken 13 down prior to the extension of Nassau Street through this area call for the removal of all building remains to 18" below grade. All basement areas, such as that of the Thompson Building, were to be backfilled with clean soil (Outline 1967). During the 1983 installation of a sewer line along the eastern edge of Nassau Street, the Department of Archaeological Research was given an opportunity to observe the soil strata along Block 4 (Samford n.d.). Remnants of the Thompson Building were evident in a concentration of brick rubble and other modern structural debris, extending to a depth of 4.5' below the modern road base. Further examination of the sewer line trench showed there to be no apparent 18th- or 19th-century soil layers along the route of the sewer line under Nassau Street (Samford n.d.).

Covington Building, and Ward L - These two structures were built south of Colonial Lots I and 3 and do not appear likely to have affected any archaeological remains associated with John Custis.

Figure 8. Building 22, which sat on the southeastern corner of the Custis property.

Figure 8. Building 22, which sat on the southeastern corner of the Custis property.

Building 22 - Known simply as Building 22, this small structure sat outside the southeastern corner of the Custis property, and appeared to be a house, perhaps for some staff member at the hospital (Figure 8).. Referred to as "the cottage" in a 1967 memo (Bridgforth 1967), it was still standing in August of 1967, although scheduled for imminent destruction (White 1967). The building does not appear from photographs to have contained a basement, and probably caused minimal to moderate damage to any archaeological remains in this area. Another smaller building (Building 23), sat directly north of Building 22, along the southern perimeter of Colonial Lot 7. Perhaps a garage or storage shed, it is likely this structure contained a shallow foundation and caused little damage to archaeological remains.3

14No other hospital buildings are recorded as having been located on Colonial Lots 1-8. Records of the 1964 excavation, however, reveal that a fair degree of disturbance from hospital activity has occurred in some of this area.

As Eastern State Hospital began to move patients to its new facility west of Williamsburg, it sold some of its grounds, including the Custis Square lots, to the College of William and Mary. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation acquired the former Custis property in 1966 from the College of William and Mary (Anonymous 1966). Since that time, no restoration of the property has taken place, with the exception of some maintenance measures at the Custis Kitchen. A brief archaeological investigation held around the kitchen area in 1964 showed the enormous archaeological potential of the lots, particularly in terms of reconstructing events on the property during the John Custis tenure. Little else has been done with the property. Although the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Landscape Department has used the southwestern portion of the lot for the dumping of topsoil, this most likely will have caused no damage to the archaeological resources contained there.

PREVIOUS ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS

Archaeological excavations have been conducted by twice on the Custis property(Block 4, Archaeological Area B) by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. The first project, conducted between March and November of 1964 under the direction of Ivor Noël Hume, explored the area around the house and standing kitchen. In addition to excavating the cellar fill of the John Custis house, an early kitchen and small outbuilding were revealed through this work (Figure 9). The 1968 work, focusing largely in the areas previously excavated, was undertaken in conjunction with the preparation of an archaeological film. Each of these projects will be briefly discussed here using information taken from maps and notes prepared during the excavations, as well as Department of Archaeology monthly reports.

1964 Excavation

Figure 10. Cross-section of rubble fill through the Custis cellar.

Figure 10. Cross-section of rubble fill through the Custis cellar.

The 1964 archaeological investigations located the cellar of the Custis House, and digging here indicated that the foundation walls of the 24' x 50' cellar had been completely robbed out for later use (Figure 10). The building had apparently been destroyed by fire sometime around 1820, and that the cellar hole, after being robbed of bricks, remained open for a short period of time, and was filled within about ten years (CWF 1964).

17 Figure 11 - Excavation around the 19th-century Custis Kitchen.

Figure 11 - Excavation around the 19th-century Custis Kitchen.

Excavation was also conducted around the extant 19th-century kitchen (Figure 11), locating in the process an earlier foundation wall running parallel with the south wall of the kitchen. This building appears to have been that of an earlier kitchen, measuring 28'7" x 24'. A walkway of broken pan tiles ran southwest from the kitchen. Both features appear to date to the 18th century.

Excavation to the south of the kitchen revealed the partial foundation of a small structure (10' x 10'2") believed to have been a dairy. Further excavation showed that it contained a small ash and clay filled pit. This was interpreted, partially on the basis of some brass waste contained within the fill of the pit, as being an ash pit under a standing furnace associated with Peter Hardy's metalworking operation. Similar industrial debris was also evident in fill overlying the earlier kitchen on the property.

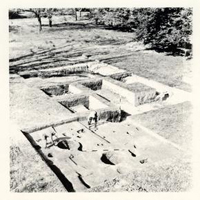

Figure 12. Overall view of the 1964 Custis excavation, showing the two wells in the foreground.

Figure 12. Overall view of the 1964 Custis excavation, showing the two wells in the foreground.

Among the most interesting features located in the 1964 work, and those providing the most information about John Custis's garden, were the two wells, located southeast of the house foundation (Figure 12). The earlier well, constructed during the first quarter of the 18th century, had been completely robbed of brick and yielded few artifacts. The second well, although filled with debris from the 1780s, contained clippings of at least sixteen species of plant material mentioned in the Custis/Collinson correspondence (A. Noël Hume 1974:31). This finding suggests that some of the garden's integrity still existed, forty years beyond Custis's death.

19Scattered units placed north and south of the house located a few other areas of interest. A vaulted drain and associated manhole, extending north from the house, appeared to have been constructed during John Custis's ownership and filled prior to the destruction of the house, around the beginning of the 19th century (CWF June 1964). South of the kitchen, in an area tested prior to the placement of the spoil pile dirt, a rammed brick roadway from the 18th century was discovered. Running north-south, and 8' wide, this feature may actually represent a path in Custis's garden. From reading the 1964 excavation notes, it appears that this area, which was only selectively excavated, contained several possible 18th-century strata or features (E.R. 1964).

Test trenches were cut with a backhoe to the east, south, and west of the main area explored in 1964, in order to determine the likelihood of encountering other structures associated with the 18th-century history of the lot. None of the trenches showed any evidence of colonial structures, although the areas southeast and east of Thompson showed a sandy clay layer containing some 18th-century artifacts. Also encountered in these trenches was the remains of what was possibly an early 19th-century hospital structure (CWF August 1964). Excavation north of the house showed that this area had been graded during the 19th century, probably to obtain fill for use in another area (CWF 1964). Other areas tested included trenches placed through the east-west ravine located north of the house, as seen on the 1781 Frenchman's Map.

1968 Excavation

Although the 1968 archaeological investigation focused largely on areas which had been excavated in 1964, twenty-two additional excavation units were examined southeast and west of the standing kitchen. This work outlined the evolution of the l8th century kitchen, as well as revealing that it was destroyed sometime around 1790. Excavation southeast of the kitchen showed that the slope was much more pronounced in the 18th century than it is today (CWF June/July 1968). Planting holes and a series of 18th century postholes, probably for fences, were defined.

Rescue Archaeology

During late 1965 and early 1966, rescue archaeology was being conducted on other portions of the Eastern State Hospital property, where 19th-century buildings were to be demolished (DeSamper 1966). It is believed that the area tested was that in the vicinity of the present Williamsburg/James City County Courthouse and not on Colonial Lots 1-8. This work was done under the direction of James Knight for the Department of Architecture and Engineering, and involved the use of cross trenching (Noël Hume 1965). The work was of a minor nature, and apparently no photographs were taken to record this project (DeSamper 1966). Upon the discovery of anything of interest, plans were made for the abandonment of cross trenching, with Mr. Noel Hume to adopt more scientific methods of excavation (Noël Hume 1965). Records indicate that no artifacts or foundations of any consequence were located through the testing (Minutes 1966).

SPECIAL TESTING

A number of scientific tests and techniques in plant identification could be used to great advantage during the archaeological investigation of the Custis property. A brief overview of some of these special techniques is presented below, with their applications to the Custis property.

Palynology

Palynology, or the recovery and study of fossil pollen, has been used with moderate success on several of Colonial Williamsburg's recent archaeological projects(Reinhard in Edwards et al. 1988; Reinhard in Samford et al. 1986). Analysis of pollen grains from archaeological soils can be assigned to family or genus levels with a fair degree of certainty (Bryant & Holloway 1983). The implications of this for the Custis site are easily recognizable, particularly since documents record a number of the plants Custis grew. There are certain limitations to pollen analysis, however, which should be kept in mind. Pollen does not survive well in alkaline soil, and then there is the problem of pollen percolating out of the soil (Reinhard in Samford et al. 1986).

Phytolith Analysis

Phytolith analysis is a relative newcomer to the field of archaeological research. Phytoliths are created from hydrated silica, present within a plant's vascular system, that conforms to the plant's cell shapes (Rovner 1983:226). Examination of these microscopic particles allows identification and possible quantification of the types of plants on a site. Phytoliths are extremely durable, and break down only in highly alkaline soil. Sampling procedures are identical to that of pollen analysis, and since phytoliths are preserved under different conditions than pollen, analysis of both will provide greater information on the plant variety on a site (Rovner 1983:225-226).

One of the shortcomings of using phytolith analysis is that at the present, most research has focused on the identification of grasses. Cataloguing new plants is a complex and time-consuming task, but phytolith research on angiosperm deciduous and coniferous trees appears promising. Not as bright an outlook is held for the taxonomic identification of dicotyledonous herbs (Rovner 1983:232).

If phytolith analysis were to be performed at the Custis Site, the identification of phytoliths for a number of additional plants would have to take place. Given the durability of phytoliths and their universal nature, it seems important to follow up in this line of research.

Remote Sensing

It has been the custom of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Department of Archaeology to use forms of remote sensing prior to conducting archaeological research on properties within the Historic Area. Different methods of remote sensing have been used with varying degrees of success since the 1960s. Apparently Ivor Noël Hume 21 conducted soil resistivity testing on the Custis property prior to beginning his excavation. Unfortunately, he states in the April 1964 Monthly Report on Archaeological Activities (CWF 1964) that brick rubble and other debris, apparently spread liberally over the lot after colonial and early 19th century hospital buildings were destroyed, had blurred the results of this testing. A recently published article discusses different types of remote sensing techniques and their applicability to archaeological sites (Weymouth 1986). Investigation of these different forms of remote sensing may reveal a method which could work around the difficulty of overburden deposits.

Infra-Red Photography

Another technique which falls into the range of remote sensing is infra-red photography. This technique is particularly useful for interpreting vegetative differences that are difficult to differentiate in regular black and white and color photographs (Ebert 1984:316).

ARCHAEOLOGICAL POTENTIAL

Research on the Custis property has led to a statement regarding the potential utility of archaeological research as a tool for recovering further information on the site; in this case for the Custis gardens and buildings. Although some areas appear to contain little potential for substantial archaeological remains (for example, the location of the Thompson Building, and the area of 19th-century grading north of the house), there are many indicators that enough undisturbed areas exist for significant research. For example, excavation notes indicate up to 3' of fill on the east side of the property (E.R. 929), and in the area of the brick roadway there were 18th-century layers and features present under the 19th-century hospital debris. Finds from test cuts south and southeast of the former Thompson Building suggest 18th-century strata in this area. If the brick roadway discovered southwest of the kitchen proves to be a garden walkway, the remains of planting beds or borders should be evident on either side of it. Tracing its route to the south and examining soil strata around it should also provide information on dating and function.

The 1964 excavation did discover, however, that the overburden on the site had been significantly disturbed by 19th-century Eastern State Hospital activities (A. Noël Hume 1984). Despite this disturbance, traces of garden activity were evident in the areas examined, and chances for locating further garden activity in unexplored areas is very great. As Mr. Noël Hume stated in the June/July 1968 monthly report "The recovery of so large a number of colonial artifacts is further evidence that a great deal of the site's history remains undisturbed beneath the surface."

Although Ivor Noël Hume's excavation located the early kitchen and a dairy, there were several other I8th-century outbuildings mentioned on the property. A meathouse and stable were standing in the late l8th century, and the 1964 archaeology did not locate these buildings. Since only limited archaeological investigations were conducted on the Custis property in the 1960s, chances of locating these and possibly other buildings in unexamined areas is very great. Perhaps most importantly, since this lot belonged to Eastern State Hospital until the late 1950s, it has never been archaeologically cross-trenched, as is common on so many of the properties within the Historic Area. In addition to this, there is no indication that anyone occupied the Custis Square lots after the first quarter of the 19th century. The relatively undeveloped nature of this property throughout the 19th and 20th centuries provides a greater chance for undisturbed archaeological strata and features dating from the 18th century.

The actual location of the garden in relationship to the house remains somewhat of a mystery. The house apparently faced what is now Francis Street, occupying a position near the center of the four-acre lot. Outbuildings revealed through archaeology and shown on 18th-century maps are located in the southwestern quadrant of the property, leading to the conclusion that most of the activities involved with running an urban plantation would be centered in this portion of the property. It is conceivable that the kitchen, or vegetable, garden would be located in or near this area. This leaves the remainder of the property for the orchard, flower, and formal gardens which Custis is believed to have cultivated. Peter Martin's (in press:90) perception of the Custis garden is as follows: 23

The southern half of the lot was where there was sufficient room for vines, vegetable, and orchards, with the vegetables, as was the custom, closest to the kitchen east of the house. The house stood a bit north of dead center in the property; it would have been most convenient to have had vehicular access to it off of Nassau Street from the west since the ground slopes steeply to the north. In that event, the drive separated the pleasure gardens north of it from orchards to the south and established at the same time the garden's principal east-west axis.

If Martin's hypothesis is correct, the enclosed area west of the house, as shown on the St. Simon's map, would have formed the garden. This spacious area, flanking Nassau Street would have been highly visible, particularly since access to the Custis House was most likely off of Nassau Street. The location of the English yew (Figure 9), which reputedly dates to the John Custis IV period, also suggests that parts of the garden were located south of, or behind, the house.

Figure 13. Series of postholes on the extreme right side of the test trench indicates the remains of a possible garden arbor.

Figure 13. Series of postholes on the extreme right side of the test trench indicates the remains of a possible garden arbor.

Custis's documents and previous archaeological research on other garden sites provides some insight into the types of features which may be expected. Even if grading or soil disturbance has taken place on some of the lot, garden beds should be evident cutting through subsoil. Also, if 18th-century soil layers are intact, we should also expect gravel walkways, as well as possible remnants of walls, fences, and arbors for the support and protection of plants (Figure 13). Various forms of cold protection devices, such as the use of heated walls, hot beds, and cold frames may be evident 24 preparation of such devices. A number of such books were included in the library of Daniel Parke Custis; these most likely had been in the library of his father, John Custis IV. Perhaps he was following their advice on the growing and propagation of certain plants; certainly we know that he had a difficult time keeping plants, particularly those sent from England by Collinson, alive due to the vagaries of the Virginia climate.

Guided by research, the results of previous archaeological investigations, and data provided through the use of remote sensing, it will almost certainly be possible to further our knowledge of the Custis property through archaeological research.

CONCLUSION

The site of John Custis's Williamsburg garden is historically important for a number of reasons. Because of the detailed documentation of plants exchanged between Custis and Collinson, this garden in a clear case of the influence of England on colonial garden planting and design. Outside of the Governor's Palace garden, it was one of the most spectacular and respected gardens in the colonies, a place English botanists and naturalists included on their travels throughout the colonies. Excavation techniques used during the archaeological investigation of the Governor's Palace precluded the gathering of the types and quality of information on plants that is possible at the present. Research and previous archaeological excavation on the property has shown that, although disturbed in some areas, the Custis site retains enough of its below-ground 18th-century integrity to warrant archaeological exploration. As it has been stated so aptly by Audrey Noël Hume, the "Custis site is the last chance in Williamsburg to extract from the ground detailed information about a major early colonial garden" (A. Noël Hume 1984).

ENDNOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1933

- Williamsburg in 1861. Typescript on file in Research Department, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1966

- Six Ancient Buildings to Tumble. Richmond Times Dispatch. April 3.

- 1967

- Memo to Mr. Peters dated August 15, 1967. In file Block 4 Eastern State Hospital 1959-1967. Department of Archives and Records, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- - n.d.

- Recent Evidence of Gardening in Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg. In Landscape Archaeology: Proceedings of the Monticello-University of Virginia Conference on Landscape Archaeology. Charlottesville. Virginia. 1986. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. In press.

- 1983

- The Role of Palynology in Archaeology. In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory Volume 6. Michael B. Schiffer, editor. New York: Academic Press 191-224.

- 1844

- Letter to Richmond newspaper.

- 1964

- Monthly Report on Archaeological Activities, March - December 1984. Copies on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1968

- Monthly Report on Archaeological Activities, May - June/July 1968. Copies on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- Letter Book of John Custis, 1717-1741. Manuscript on file, Library of Congress, Washington D. C.

- 1966

- Memo to Files, dated 3-14-1966. In file Block 4 Eastern State Hospital 1959-1967. Department of Archives and Records, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA. 28

- 1782

- Cartes des Environs de Williamsburg en Virginie on les Armees Francoise et Americaine on Campes en Septembre 1781. [By] Desandrouins Armie de Rochambeau, 1782. Original in Library of Congress, Rochambeau Map #57.

- 1984

- Remote Sensing Applications in Archaeology. In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory Volume 7. Edited by Michael Schiffer. Academic Press, New York. pp. 293-362.

- 1988

- Archaeology of the Peyton Randolph Houselot. Draft report on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1964

- Excavation Register of the Custis Site Excavation, E. R. 750-779, 782-836, 850-906, and 907-933. Department of Archaeology. Notes on microfilm roll TT-001.001, Department of Archives and Records, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1782

- Plan de la ville et environs de Williamsburg en Virginie, 1782. Photostat copy of map on file, Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- Galt Family Papers. Original documents on file at the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA.

- Galt Papers, File on Financial Matters and Appropriations. On file at the Patient's Library, Eastern State Hospital, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1974

- The Public Hospital, 1766-1885 [Eastern State Hospital] Block 4, Colonial Lots 80-87. Report on file at Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1987

- Archaeological Investigations of the Shields Tavern Site, Williamsburg Virginia. Draft report on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1972

- A Report on Exploratory Excavations at Carter's Grove Plantation, James City County, Virginia (June 1970-September 1971). Unpublished report on file, Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA. 29

- 1984

- Landscape Archaeology: A Key to Virginia's Cultivated Past. In British and American Gardens in the Eighteenth Century. Eighteen Illustrated Essays on Garden History. Edited by Robert P. Maccubbin and Peter Martin. Williamsburg: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1986

- Interpreting Ideology in Historical Archaeology: The William Paca Garden in Annapolis. Paper presented at the Monticello-University of Virginia Conference on Landscape Archaeology, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1986.

- 1987

- The Archaeology of a 17th-Century Garden at Bacon's Castle. Paper presented at "Design of the Land" Garden History from the 17th Century to Colonial Revival Period. Historic Petersburg Foundation Conference, March 6-7, 1987.

- in press

- From Jamestown to Jefferson: The World of Virginia Gardening. In press.

- 1966

- Minutes of Architecture, Construction and Maintenance Division Meeting, March 8, 1966. In file Block 4 Eastern State Hospital 1959-1967. Department of Archives and Records, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1974

- Archaeology and the Colonial Gardener. Colonial Williamsburg Archaeological Series No. 7. Williamsburg: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1984

- Memo to Beatrix Rumford, dated 3-29-1984, on the Archaeological Potential of the Newport Avenue Parking Lot. On file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1965

- Memo to E. M. Frank dated September 23, 1965. In file Block 4 Eastern State Hospital 1959-1967. Department of Archives and Records, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1967

- Outline Specifications for Removal of Structures on Eastern State Hospital and College Property-Area C. 8-16-67. In file, Block 4 Eastern State Hospital 1959-1967. Department of Archives and Records, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1986

-

Palynological and Parasitological Investigations of Soils from Tazewell Hall, Williamsburg, Virginia. In Archaeological Excavations on the Tazewell Hall Property. Patricia Samford, Gregory Brown and Ann Smart. Report on file at the Department of Archaeological Research. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

30 1988 Pollen and Parasite Analysis of the Peyton Randolph Site, Williamsburg, Virginia. In Archaeology of the Peyton Randolph Houselot. Andrew Edwards, Linda K. Derry and Roy A. Jackson. Draft report on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA. - 1983

- Plant Opal Phytolith Analysis: Major Advances in Archaeobotanical Research. In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory. Volume 6. Michael B. Schiffer, editor. New York: Academic Press. 225-266.

- n.d.

- Nassau Street Sewer Line Project. Draft archaeological report on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1986

- Archaeological Excavations on the Tazewell Hall Property. Report on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1781

- Carte de la Campagne de la Division aux ordres du Mis St. Simon en Virginie. Ayer Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago.

- 1959

- Custis Square; Block 4 Colonial Lots 1-8, Francis Street. Report on file at the Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1957

- Brothers of the Spade: Correspondence of Peter Collinson of London, and of John Custis, of Williamsburg, Virginia. 1734-1746. Barre, MA: Barre Gazette.

- 1771

- Purdie & Dixon, editors. June 20, 1771.

- 1778

- Dixon & Hunter, editors. November 27, 1778.

- George Bolling Lee Papers, 1701-1924. Microfilm reference M1073.5. Virginia State Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia.

- 1986

- Geophysical Methods of Archaeological Site Surveying. In Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory. Volume 9. Edited by Michael Schiffer. Academic Press, New York. pp. 311-395. 31

- 1967

- Memo to B. B. Bridgforth, dated 12-18-1967, with attached map "Status of Buildings in Blocks 4 & 44 (E.S.H. Prop.), August 16, 1967". In file, Block 4 Eastern State Hospital 1959-1967. Department of Archives and Records, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

- 1958

- The London Diary of William Byrd of Virginia (1717-1721). New York.

- 1984

- Contrary to Nature: The Calvert Orangery as a Symbol of Power for a Patrician Household in Annapolis, Md. Paper presented at the 45th Conference on Early American History "The Colonial Experience: Eighteenth Century Maryland", 13 September 1984, Baltimore, MD.